Recommendations for Increasing PrEP Uptake Among Young Cisgender Black Women

PrEP, or Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, is a highly effective medication for preventing HIV infection. However, low usage of PrEP is a major concern among some populations most at risk for HIV. Given the disproportionate burden of HIV among young Black women, health care professionals should work to increase PrEP uptake and adherence using strategies tailored for specific populations.

This brief first highlights key findings from the authors’ review of data on HIV diagnoses and use of PrEP among young Black women who are cisgender, or those whose current gender is the same as that which they were assigned at birth. We include recent statistics on HIV diagnosis by race, gender, and age, along with statistics on PrEP use by race and age. We then share findings on barriers to PrEP use—from both health care providers’ and patients’ perspectives—and conclude with recommendations for health care, public health, and research professionals on increasing PrEP uptake.

Overview of PrEP and HIV Diagnosis

In HIV-negative individuals, PrEP can be taken as a daily pill or as an injection every two months and is useful for anyone who is at risk of HIV infection through sexual activity or injecting drugs. And because PrEP does not require cooperation between partners in the same way as condoms or viral suppression,[1] it represents an autonomous preventive HIV measure one can control on their own.

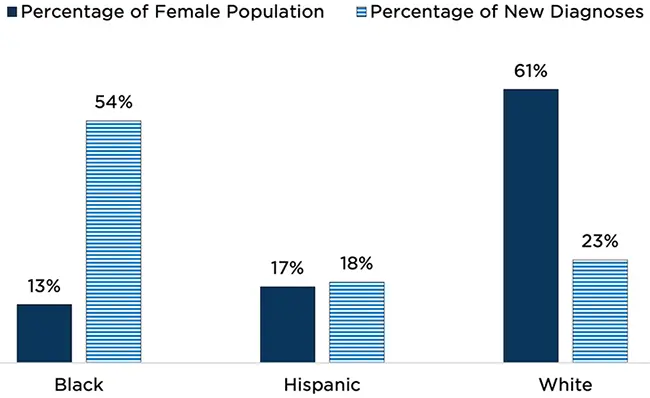

However, discrepancies in the prescription and use of PrEP among those most at risk for HIV—specifically for our analysis, young cisgender[2] Black women—are cause for concern. According to 2021 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) HIV Surveillance Report, Black cisgender women represented 13 percent of the female population in the United States in 2021 but made up 54 percent of new HIV diagnoses among cisgender women (see Figure 1). This discrepancy is the result of a complex interplay of factors, including stigma, socioeconomic factors, and prevalence of HIV and STIs within Black communities. By comparison, Hispanic women represented 17 percent of the female population and 18 percent of new diagnoses, while White women represented 61 percent of the female population and 23 percent of new diagnoses.

Figure 1: Black women represent a disproportionate share of new HIV diagnoses compared to Hispanic and White women

Percentage of new HIV diagnoses and percentage of female population in 2021, by race

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). HIV Surveillance Report, 2021; vol. 34. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html.

Table 2a: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance/vol-34/content/tables.html

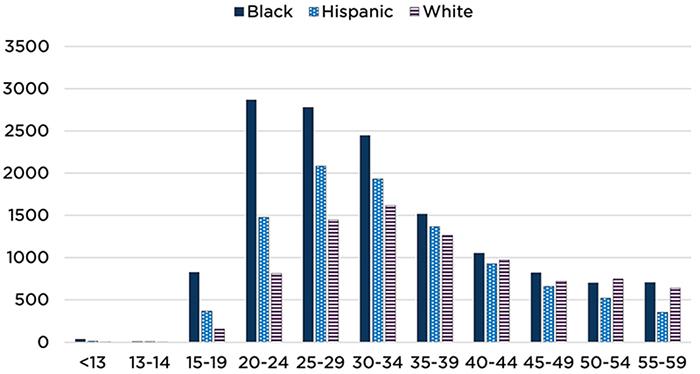

In addition, in 2021, 19 percent of all new cases of HIV were within individuals ages 13 to 24; in other words, one out of five people who have been diagnosed with HIV was under age 24. When viewing this data by race (see Figure 2), it becomes clear that Black individuals are disproportionately diagnosed at younger ages than their Hispanic and White counterparts.

Figure 2: Young Black individuals ages 13 to 24 experience a greater number of new HIV diagnoses than White and Hispanic individuals

Number of HIV diagnoses (inclusive of all genders) by age at first diagnosis and race, 2021

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). HIV Surveillance Report, 2021; vol. 34. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html.

Table 2a: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance/vol-34/content/tables.html

Dissemination of data inhibits understanding of HIV incidence for cisgender and transgender individuals

In disseminating statistics on new HIV infections, the CDC releases accessible infographics combining all people who were assigned female at birth based on sex characteristics, which means transgender[3] men and some nonbinary people were also included in data reported to represent women.

Diving deeper into the data, the numbers of transgender men and individuals of genders other than “male” or “female” (who could be of any sex) make up a very small portion of the population included in the CDC reports. Separating transgender men from the “female” population does not change the percentages reported in this brief. However, differentiating respondents by gender does play an important role in accurately characterizing populations affected by HIV and preventing the erasure of trans identities.

In addition, rates of HIV in transgender women are higher than among the general population and, when grouped by sex assigned at birth, this discounts not only their identity but erases them from broader public health efforts for screening, treatment, and care.

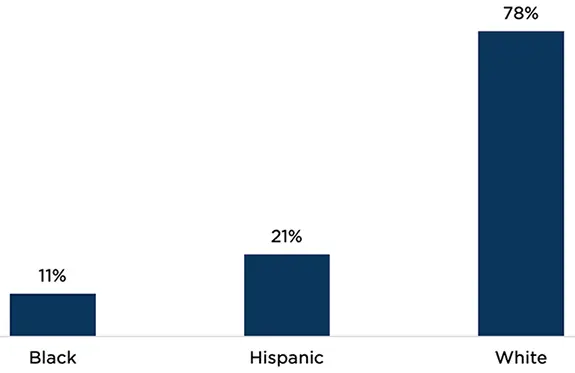

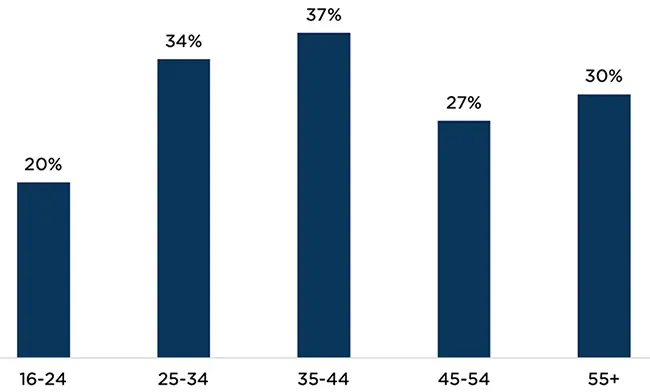

Furthermore, PrEP uptake among Black individuals is especially low. Of those for whom PrEP is indicated—in other words, those for whom it is considered medically reasonable to administer PrEP—only 11 percent of Black individuals were using PrEP in 2021, compared with 21 percent of Hispanic individuals and 78 percent of White individuals (Figure 3a). Broken down by age group, PrEP uptake was lowest among younger populations, with only 20 percent of those ages 16 to 24 for whom PrEP is indicated actually using the medication (Figure 3b). While data on PrEP uptake in Black cisgender young women are not directly available, these figures indicate that PrEP use is lowest in both Black and young populations, leaving those with the greatest likelihood of contracting HIV also the most unprotected. Combined with the disproportionality in diagnoses within cisgender women, we can infer that young, Black, cisgender women are less likely to use PrEP despite the higher likelihood of contracting HIV in this population.

Figure 3a: Black individuals represent a disproportionately low share of PrEP users among those indicated for PrEP use, compared to Hispanic and White individuals

Percentage of individuals indicated for PrEP use who are using PrEP, by race

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 dependent areas, 2021. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report, 28(4). http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html.

Table 9a: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance/vol-28-no-4/content/tables.html

Note: Coverage is calculated by dividing the number of individuals on PrEP by the number of individuals for whom PrEP is indicated. A treatment is considered “indicated” if it is medically reasonable to administer in a given situation.

Figure 3b: Young people (ages 16 to 24) represent a disproportionately low share of PrEP users among those indicated, compared to individuals of other ages

Percentage of individuals indicated for PrEP use who are using PrEP, by age group

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 dependent areas, 2021. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report, 28(4). http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html.

Table 9a: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance/vol-28-no-4/content/tables.html

Note: Coverage is calculated by dividing the number of individuals on PrEP by the number of individuals for whom PrEP is indicated. A treatment is considered “indicated” if it is medically reasonable to administer in a given situation.

Barriers to PrEP Uptake

To examine what is known about providing and improving uptake of PrEP among Black cisgender women, Child Trends and the University of Missouri, Kansas City conducted a literature review of studies published from 2014 to 2023. Using PubMed, EbscoHost, and CINHAL databases, the team identified 157 abstracts and assessed the full articles across a number of criteria for inclusion. Of the 157 articles, 29 were ultimately chosen for full review and included in our analysis. A peer-reviewed scoping review article is forthcoming; in the meantime, highlights of our analysis are below.

Research suggests there are multiple barriers for both providers and patients that limit PrEP uptake among Black cisgender women. In our review of the literature, several themes emerged for why there is inadequate prescription and use of this preventive HIV medicine.

Provider barriers

For health care providers, the research highlights the following top barriers to prescribing PrEP:

- Lack of provider knowledge in terms of PrEP guidelines and side effects[4]

- Discomfort discussing sexual health, HIV, and/or drug use with patients[5]

- Competing needs during patient appointments[6]

- Concerns that the patient will be uncomfortable discussing sexual behaviors, sexuality, HIV, and/or drug use[7]

- Age, gender, and racial biases, including providers’ assumptions about patients’ behaviors (or lack thereof)[8]

- Lack of continuity of care and time needed for follow-up with patients[9]

- Concerns about the cost of PrEP to patients[10]

Patient barriers

The literature we reviewed focused most heavily on patient barriers, a framing that incorrectly presumes that a patient’s lack of PrEP use is more an individual than a structural or systematic issue and places more responsibility on the patient than on trained, professional providers. Barriers from the patient-centered perspective include the following:

- Low awareness of their individual risk of acquiring HIV[11]

- Lack of PrEP knowledge[12]

- Concerns about cost[13]

- Concerns about interactions and side effects[14]

- Concerns about their ability to adhere to daily regimens[15]

- Low confidence in PrEP’s efficacy[16]

- Medical mistrust[17]

- Concerns about stigma and/or judgement from partners, family, and/or friends[18]

Recommendations for Health Care, Public Health, and Research Professionals

Health care and public health professionals and researchers can help increase knowledge of, access to, and uptake of PrEP among Black women, and especially among young cisgender Black women. Below are several recommendations to increase use of and adherence to this preventive medicine:

Health care professionals

Clinicians need more formal education in nursing and medical school and continued professional development in sexual health, including how to take a sexual history using practical, comprehensive tools. A 2020 narrative review published in Sexually Transmitted Diseases found that sexual histories were obtained in less than one third of clinic well-visits and in anywhere from 8 percent to 82 percent of visits for which clients presented with a STI-related or genitourinary/abdominal complaint.

Once trained, health care providers need to integrate age-appropriate comprehensive sexual health assessments into routine care to better understand their patient’s sexual health, risks, and needs; determine frequency of STI/HIV screenings; and guide counseling. These conversations must be normalized with every patient to help end the stigma and shame associated with STIs and HIV. Additionally, providers must talk with patients about PrEP and its effectiveness, the various ways in which it can be administered (i.e., daily, injectable, oral), the side effects of PrEP, and the cost. Providers also cannot make assumptions about a person’s partners, HIV status, substance use, and behaviors based on their age, sex, gender, or race/ethnicity. Providers must start assessments early in their relationship with a patient and routinize them over time as they build rapport.

Thorough sexual health assessments are also critical for accurate data on the percentages of female PrEP users. The CDC calculates percentages by dividing the number of people prescribed PrEP by the number of people with indications for receiving PrEP. Findings from our literature review suggest that the reported number of people with indications for PrEP is likely to be dramatically lower than the actual number, due to a lack of screening and gender and racial biases among providers.

Public health professionals

Public health professionals need to improve and expand their messaging about PrEP to cisgender young women to increase their awareness and knowledge. Sales et al. (2019) point out that men who have sex with men have been the main audience for highly visible PrEP awareness campaigns and, although some recent campaigns include messaging directed to women, these campaigns are small and have not penetrated the cultural zeitgeist. Such campaigns must address misinformation and misconceptions about HIV and PrEP; introduce the various forms of the medicine, including oral and injectable PrEP; and be inclusive of adolescent and young adult audiences.

Researchers

Researchers need to report and disseminate data on PrEP uptake accurately and responsibly. By combining data from cisgender and transgender people by sex assigned at birth, researchers misgender transgender people and inaccurately report findings, which have critical consequences for understanding patterns of HIV acquisition.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Lizy Wildsmith, Kristen Harper, and the UMKC Collaborative to Advance Health Services for their invaluable guidance regarding the overall framing of this product, for reviewing drafts, and for providing feedback throughout its development; Brent Franklin for editorial review and feedback on structure; Hannah Lantos for an equity review; Dominique Martinez for fact checking; and Jessica Conway for copyediting.

Footnotes

[1] Viral suppression is a reduction in the number of copies of a virus within the body. For more information, see: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/art/index.html#:~:text=If%20taken%20as%20

prescribed%2C%20HIV,HIV%20per%20milliliter%20of%20blood

[2] “Cisgender” is a term that describes individuals whose current gender is the same as that which they were assigned at birth based on physical sex characteristics.

[3] “Transgender” is a term that describes individuals whose current gender is different from that which they were assigned at birth based on physical sex characteristics.

[4] Hill et al. (2022), Jackson et al. (2022), Kurek et al. (2022), Pratt et al. (2022), Sales et al. (2019)

[5] Hill et al. (2022), Jackson et al. (2022)

[7] Arnold et al. (2022), Jackson et al. (2022)

[8] Bunting et al. (2022), Hill et al. (2022), Jackson et al. (2022), Kurek et al. (2022), Pratt et al. (2022), Tessema et al. (2021)

[9] Jackson et al. (2022), Pratt et al. (2022)

[10] Hill et al. (2022), Johnson et al. (2022), Pratt et al. (2022)

[11] Arnold et al. (2022), Chandler (2020), Haider et al. (2022), Johnson et al. (2020), Koren et al. (2018), Kurek et al. (2022), Mangum et al. (2022), Pearson et al. (2020), Scott et al. (2022)

[12] Arnold et al. (2022), Carley et al. (2019), Chandler (2020), Hirschhorn et al. (2020), Johnson et al. (2020), Koren et al. (2018), Kurek et al. (2022), Raifman et al. (2019), Sales et al. (2019), Scott et al. (2022), Tekeste et al. (2019)

[13]Arnold et al. (2022), Haider et al. (2022), Hirschhorn et al. (2020), Jackson et al. (2022), Johnson et al. (2020), Koren et al. (2018), Willie et al. (2021)

[14] Carley et al. (2019), Chandler (2020), Haider et al. (2022), Hirschhorn et al. (2020), Jackson et al. (2022), Johnson et al. (2020), Koren et al. (2018), Pearson et al. (2020), Willie et al. (2021)

[15] Carley et al. (2019), Hirschhorn et al. (2020), Jackson et al. (2022)

[16] Hirschhorn et al. (2020), Kurek et al. (2022)

[17] Tekeste et al. (2019), Willie et al. (2021)

[18] Arnold et al. (2022), Chandler (2020), Hirschhorn et al. (2020), Jackson et al. (2022), Scott et al. (2022)

Suggested citation

Rogers, J., Schaefer, C. (2023). Recommendations for increasing PrEP uptake among young cisgender Black women. Child Trends. DOI: 10.56417/8118n2999r

© Copyright 2024 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInThreadsYouTube